Well, would you look at that, my 20th post. Before I kick off, I’d just like to say thank you to all my subscribers, followers and casual drop ins—you’re all very much appreciated and keep me coming back to this space week after week.

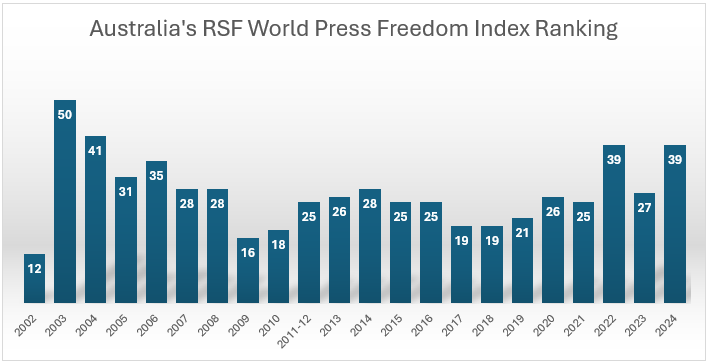

Since we last met, it has been revealed that Australia has dropped to 39th place in the World Press Freedom rankings from 27th last year. The size of the fall was somewhat of a surprise given the dire situation journalists—and more broadly, humanity—face in other parts of the world, particularly those bludgeoned by war or suppressed by dictatorships. So this week I’ve been digging around in the numbers to find the reason, and thinking about what the future holds for Australian media.

The World Press Freedom Index is released annually by Reporters Without Borders (known in French as Reporters sans Frontières, or RSF), an international non-profit organisation based in France that works to protect press freedom. Australia dropped 12 places in 2024 to rank 39th out of 180 countries, of which Norway, ranked 1st, was the country with the greatest press freedom, and Eritrea, ranked 180th, was the worst. Overall, Australia’s press freedom was graded as ‘satisfactory’ with a score of 73.42 out of 100, down from 78.24 in 2023.

So what caused the decline?

Before digging into the reasons, I should highlight that firstly, the WPF Index is very volatile with frequent large swings, and secondly, the methodology used to determine the index changed significantly in 2022, which makes it hard to compare current rankings with those of the past. Nevertheless, the data remain a useful indicator of the ebbs and flows of interference, albeit with what appears to be a lag behind triggering events.

RSF says there are several ways press freedom can be impinged. It may be caused by restricting the ability of journalists to “select, produce, and disseminate news in the public interest,” and such restrictions may be as a result of “political, economic, legal and social interference”.

It doesn’t highlight any single event that caused Australia to fall in the rankings in 2024, but provides this general overview:

“Press freedom is not constitutionally guaranteed in this island-continent of 26 million people, but a hyperconcentration of the media combined with growing pressure from the authorities endanger public interest journalism.”

It’s a bit of a mixed bag, so let’s look at some of the issues as broken down by political, economic, legal and social interference.

Political and legal factors

As you can see from this chart I pulled together, Australia’s lowest ranking of 50 in 2003 occurred during a time of political interference by the Howard Government, which prevented journalists from accessing and reporting on refugees held in detention centres both on and off Australian soil. The country’s ranking improved around the end of the Howard era in 2007 and remained stable until 2022.

Sentiment among journalists in Australia started to turn in 2019 when the Australian Federal Police, under the Morrison Government, raided journalist Annika Smethurst’s home with a warrant that the High Court later found to be invalid. Another blow came this past year when the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) succumbed to pressure from the West Australian police to hand over footage of climate protesters that is believed to have been used to make criminal charges against the protestors involved.

On the flipside, media companies were successful in staving off two very high-profile defamation lawsuits in the past year; one brought by soldier Ben Roberts-Smith accused of war crimes, and the other by political staffer Bruce Lehrmann accused of rape.

For the most part, Australia’s legal system has upheld press freedom, and there is no reason to suspect any imminent change in this regard. Even so, the potential for erosion is always there lurking in the shadows, and nothing illustrates this more than the Federal Government’s annual budget allocation to the country’s national broadcaster, the ABC, which has become a bit of a cruel sport.

Political interference can be unnerving, but the biggest threats to Australia’s press freedom currently don’t lie in the political sphere. They are found somewhere much harder to control.

One hand clapping

All the journalists in the world have little impact if they don’t have an effective means of communicating their stories, and in Australia, economic and social shifts now pose the biggest threats in that regard.

Around 60,000 jobs were lost across Australian media and information industries between 2007 and 2019, and 28,000 of those losses were in publishing alone, a report called The Future of Work in Journalism showed.

All indicators suggest that trend has continued with devastating consequences in regional Australia. More than 200 local news outlets have suffered contractions or closures since 2019, the majority of which have been in regional Australia, according to research at the University of Canberra. The research demonstrates a link between the disappearance of local news services and a disconnection between people and their communities coinciding with an increase their distrust of the media.

Sadly, we’re doing it to ourselves. Society is choosing to leave traditional media behind in favour of digital platforms, rendering the former unprofitable.

In Australia, the result has been the consolidation of corporate media into a duopoly between News Corp and Nine Entertainment, the latter acquiring Fairfax in 2018. Rather alarmingly in 2020, the two companies, which were shareholders in Australia’s national newswire, Australian Associated Press (AAP), pulled the pin on the critical news service, which provided news, images and video to around 200 newspapers, broadcasters and websites. Given that AAP was a viable business, the move was largely seen as a means of damaging competition from smaller news services, particularly regional news outlets, that relied heavily on the newswire. A consortium stepped in to rescue the news service, but what remains of the company is a shell of its former self. The damage had been done.

The digital revolution

While one might look at the internet and laud the ability of anyone and everyone to publish, such as I am doing right now, for many, the ability to reach a significant audience is minimal. Add to that the proliferation of those who intentionally seek to stir the pot with misinformation, and you’ve got a tempest of information that most people aren’t equipped to sail through.

Younger generations in particular are disconnecting from reliable sources of news. Figures from the Australian Communications and Media Authority showed that 46% of 18 to 24-year-olds nominated social media as their main source of news in 2023. Of those, 31% said they relied on celebrities and social media influencers for their news content. The report doesn’t examine the credibility of the news sources.

Across all ages, 20% of Australians now cite social media as their main source of news, up from 17% in 2022.

Of course, such structural change isn’t confined to Australia. It’s a global trend.

Future present

To see the potential such social shifts can have on press freedom, one only needs to look across the ditch to New Zealand, which despite what I’m about to point out, still ranks higher than Australia on the World Press Freedom index at number 19.

New Zealand has recently suffered a crumbling in broadcast news, which overtime has succumbed to the closure of all free-to-air TV news services with the exception of the national broadcaster, TVNZ, which has also slashed its news department and cut back on bulletins.

The most concerning part about all this is the dislocation such breakdowns form within society itself.

Let’s take the research by The University of Canberra mentioned previously and apply it at a national level. We can consider the loss of news services to consist of both physical loss—as in job losses, downsizing, loss of news diversity, and service closures—as well as the loss of audience due to social shifts. To make my point, I have redacted the word ‘local’ from this quote from the report:

“Typically, in areas where there have been

localmedia closures, there is less news reporting onlocalgovernment activities, courts, health and education issues relevant to the community. This decline in news provision weakens the democratic system becauselocalcommunities are devoid of critical information and there is less accountability. Therefore, citizens have fewer opportunities to engage with the community and participate in public discourse. Eventually, this lack of exposure can lead to people losing a personal connection with the topics that are important to them. This leads to the first set of hypotheses related tolocalnews closures and the impact on the community:H1. Closure of

localnews media will be negatively related tolocalaudiences’ community attachment.H2. Closure of

localnews media be negatively related tolocalaudiences’ trust in news.”

As I read the above lines, my mind moves toward the Presidential elections in the United States, the rise of MAGA, distrust of the media, civil unrest and impingements on social freedoms. The US ranks at number 55 in the World Press Freedom Index, with a score of 66.59, falling within the class of ‘problematic’.

It demonstrates the importance that Australian governments realise that funding independent news services across all pockets of the country is imperative to maintaining a strong and stable society held together by a sense of involvement and community, and that our education systems need to equip young people with the skills to navigate the turbulence of online information in order to access reliable news. Economic and social forces left to their own devices will only work to reduce press freedom and heighten the risk of social breakdown.

Things I’ve enjoyed reading on Substack this week

Then They Came For Rafah—by Frederick Joseph

A timely and sobering analysis that comes in a week where Israel shut down news service Al Jazeera, impinging upon press freedom, and in which Yahoo News jammed the assault on Rafah into the same news flash as the Met Gala.

A Woman Hidden in History—by Elif Shafak

Lou Andreas Salomé has been remembered as ‘the muse’ to a number of men lauded by history, and in doing so, her brilliance has been masked over.

Blind Spot—Chapter 1—by Steve Fendt

It’s the perfect week to jump aboard the serialised short-story bandwagon, with the first chapter of Steve’s latest tale having just gone live.

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment below, click the ❤️ button, or share it with someone who would appreciate it.

I’ll be back next week. Until then, keep 💪.

Yes Alia, your first-rate analysis highlights how discernible slumps in press freedom are a consequence of monopolisation of information as a commercial or ideological product. The clarity of your examination of the local and global picture indicates that Australian media is struggling to respond to the increasingly rapid pace of change and unprecedented complexity. Thank you for turning your mind to useful steps for reform.

Thank you for joining some dots for me here, putting some things I was vaguely (too vaguely!) aware of in context. And thanks also for the mention of Blind Spot😊