There really is a mystery at Hanging Rock

#04 — And it has nothing to do with schoolgirls.

The rose-tinted columns of rock, cool and damp in the forest shade, reach like fingers toward the clouds and disappear above the trees. I walk alongside the base of these giant figures, their feet moulded as one, frozen in time, yet, as I move, their bodies bend and curve in a transcendent dance.

The path to my right has been worn by footsteps that reach far back in time, and following it, I round a bend to where two sentinels part ways to reveal a staircase winding upwards through the soothing shadows and out of sight. I take a step and stop to trace my fingers along the rock’s lichen speckled surface. It is bumpy, but not rough. My baby, strapped to my chest, reaches her hands out to feel it too. Ahead in the unknown, the sound of my three-year-old warbling with my husband breaks the hum of the bush and I begin to climb toward them.

It's near impossible to visit this mesmerising feature of the Australian landscape without our thoughts being invaded by visions of schoolgirls moving ghostlike between these ancient weather-worn shapes in flowing white dresses of muslin and lace. For many, the mystery created by author Joan Lindsay in her 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock endures. How could three schoolgirls and a teacher, on Valentines Day 1900, disappear among these rocks without explanation?

There are many reasons this story has become engrained in Australian mythology. Peter Weir’s masterful screen adaptation of the same name in 1975 brought the story to the masses, etching into our minds images of innocent girls, subjects of the British Empire, their white skin and white dresses moving in a hypnotic trance through the beautifully harsh, mystical and unforgiving Australian landscape. They are surrounded by Country they don’t understand – that colonial Australia fails to understand – and from that incomprehension, there is perceived danger. The story plays upon colonial Australia’s fear of the bush and its associated mysticism.

The clincher, however – the reason this story endures – is because of its mystery: the girls are never found, there is no explanation, and there’s the dangled possibility that this all might be true. Lindsay teases the brain into obsessively trying to solve the unsolvable.

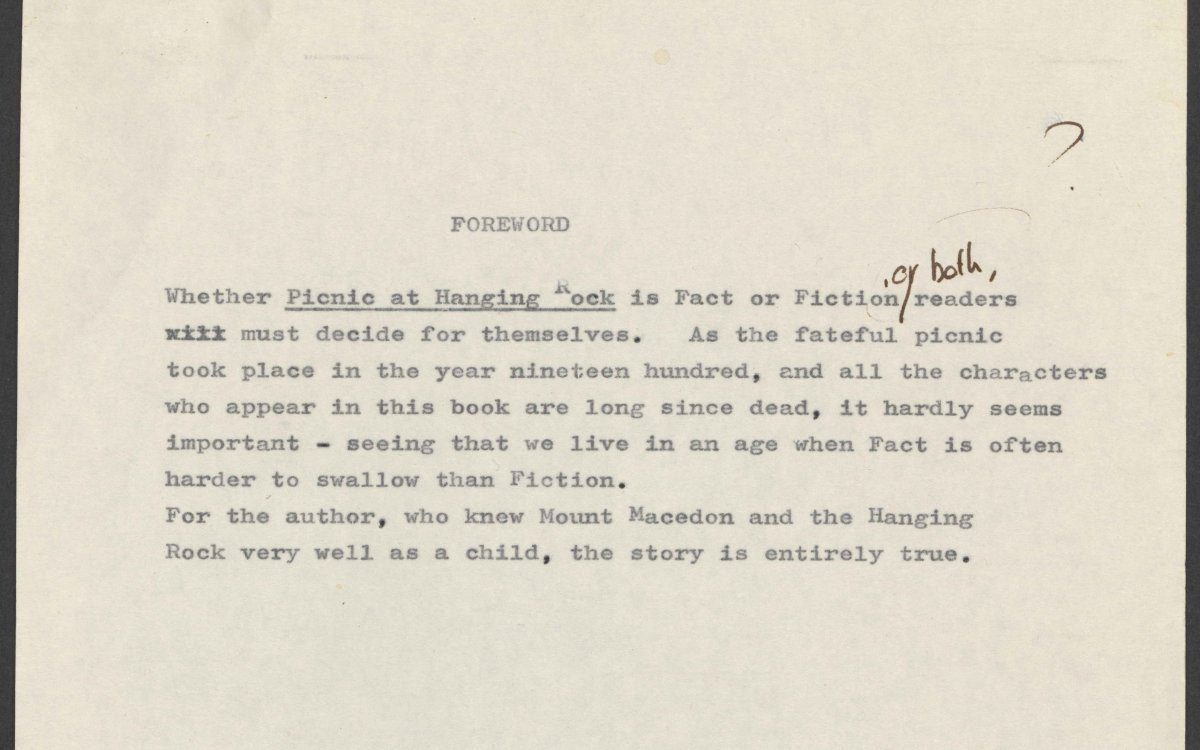

As a writer, Lindsay knew the power of an unsolved mystery, especially one draped in truth. In the forward to the novel, she wrote:

“Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important.”

Lindsay refrains from declaring the story to be true, but she doesn’t deny it. It’s an invitation to believe.

I pause in front of a timber sign in aged green paint that says, ‘Hanging Rock’, and indeed, a tremendous boulder spans bridge-like above us, wedged between the even larger towers of rock enveloping us in this crevice. A step further and I notice a small plaque to: "A young boy who loved life, always remembered. 1989-2002”.

My heart sinks. The disappeared schoolgirls and the tragedy that bears down on those connected with them brings many to this place. But the story is fictional (yes, as much as some may want to believe), it’s not real.

This little boy, was.

This volcanic marvel of nature, towering to 711 metres above sea level, has its dangers with slippery rocks and steep drops. I call to my husband ahead to make sure he’s holding the hand of our fearless adventurer who is no doubt doing all she can to run away to explore. And she is.

A few more steps and we emerge into a sunlit natural platform bordered by large rocks, some rounded, some softly pointing. Some have broken free, but they are mostly forged together for eternity by the molten lava that created them. They surround the platform like a castle parapet from through whose crenels is revealed a delightful pastoral view dotted with hay twirled in circular bales.

We had stopped at Hanging Rock on a whim while driving to Melbourne, attracted by its fictional legend like throngs of others. I, like most other Australians, knew little of this place other than the dreamlike scenes from Weir’s film remembered from some thirty years before.

Only a third of the way up and the magnetism of the place has captivated me. I press my hand against the rock and sigh. I sigh with sadness and recognition that this place has stories no ear shall ever hear. I sigh because everything about this place tells me it is sacred: its rare soda-trachyte lava tendrils, its mesmerising formations, its precarious chasms, its freshwater spring, and its towering vantage over Country. I can point to my location on a map, but in truth, I have no idea where I am. Places like this are always for the initiated; for those who understand and respect their significance. It feels like other places I know of reserved for men’s business, and, if the old lore was in force, I’m certain now I shouldn’t be here.

There is a mystery to Hanging Rock and it’s one that has nothing to do with pubescent schoolgirls. And it’s a mystery that’s sadly not unique; it’s a reoccurring theme at sacred sites all over Australia, white-washed of the stories that travelled with them for tens of thousands of years.

The informative display at the base of Hanging Rock overwhelmingly focused on Lindsay’s novel. I recall a short recognition of the site’s traditional custodians, but there was no further insight into its importance as a sacred site. (I will confess, I was required to pass through the display at three-year-old speed and possibly missed it, but if it was there, it was dwarfed by the fictional. My suspicions are given credence by a campaign by RMIT researcher Dr Amy Spiers called ‘Miranda Must Go’ (Miranda being one of the central characters of the book), which made a similar observation and seeks to elevate the site’s traditional history above that of the novel.)

Later, at my computer, I go in search of the missing information and dig up a familiar story.

Hanging Rock, also known as Mount Diogenes, sits at the border of Dja Dja Wurrung, Woi Wurrung (Wurundjeri) and Taungurung Country. It is believed to have been a sacred site and meeting place for each of them, and discoveries of stone tools – some having travelled songlines from faraway places – show their ancestors to have used this place for at least 10,000 years, and likely much longer.

Tragically, the colonial era erased much of what’s known about this mysterious place, replacing it with captivating stories that evoke Missing White Woman Syndrome, and fashioning a horse racing track and sports oval at its base. Yes, sporting events have been held in this bushland location from the late 1860s. That’s not as strange as it sounds. Many Australian racetrack and sporting ovals to this day occupy ancient corroboree and ngargee grounds, large spaces perfect for social gatherings, conveniently flattened by the feet of thousands over time. And this was probably the case at Hanging Rock.

But what did the First Nation’s peoples call this volcanic formation? And what is its significance?

Ngannelong has emerged as the most respectful name for this sacred site, although what it means and which language it comes from is believed to be lost. The name is derived from the word “Anneyelong”, inscribed under an etching of the formation by German naturalist William Blandowski who travelled through the area in 1855, and amended to Ngannelong by linguists.

Theatre producer Jason Tamiru of the Yorta Yorta Nation and Dja Dja Wurrung, Yang Bulug Mob said:

“At first, I refrained from naming the Rock due to the reality of seeing it listed differently in a number of different places. After speaking to family, the rightful name of Hanging Rock is Ngannelong.

Picnic at Ngannelong.

The truth is my people were hit hard during the frontier wars. The Western region is known to us as the Killing Fields. The naming of the Rock is with all those that come in my dreams. Australia is starting to learn that there is a black history in this country that needs to be acknowledged and celebrated.”

It's likely Ngannelong was known by different names by the Nations and clans surrounding it, and each would have had its own stories and lore attached to it. Much of the knowledge about Ngannelong was lost with the widespread Frontier War killings combined with disease, then by the White Australia policy that removed generations of children from their families, breaking the chain of oral history. But some knowledge remains.

Recorded in the Hanging Rock Strategic Plan, September 2018, is a creation story shared by Taungurung Elders that confirms, from their perspective, the importance of Ngannelong as a place to initiate boys into manhood. It goes:

“The wiylak (young boys) were gathered together and sent to a ceremonial site near what is now known as Hanging Rock today. This site was used for performing male initiations. The underground spring water was used to cleanse their bodies for the ceremony as well as mix the ochre for decorations.

The wiylak didn’t know what was expected of them. Bundjil sat them down and explained everything. There was a wiylak named Goorbil and he was misbehaving. Bundjil was furious because these initiations were so important. It was so important for wiylak to become young gulinj. Bundjil pulled Goorbil aside and told him to behave or, “I will turn you into stone, like the other wiylak”.

Bundjil said to Goorbil, “Do you see those rock formations there? Well they are other young boys that did not do what they were told. They had no respect for the Law of the land and people.”

Goorbil did what he was told and did not misbehave again and all the wiylak went through their initiations and became young gulinj.”

The strategic plan is the only resource that appears to document these facts. It also sets out a plan to elevate the information on the First Nations’ cultural use and history of Ngannelong to its rightful place.

More than five years later, my visit to the site this month saw no evidence of that. Not yet. For now, Joan Lindsay’s literary feat Picnic at Hanging Rock, its mystery and its baiting of truth, continues to dominate this ancient wonder of the Australian landscape, suppressing the site’s true history to the realms of those who go looking for it.

Earlier, I quoted Lindsay’s forward for the novel in which she said the truth “hardly seems important.” Her original transcript continued this sentence with words removed by her editor. They read:

“ — seeing that we live in an age when Fact is often harder to swallow than Fiction.”

And right she was.

Thanks for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment below, show some ❤️, or help me get this new publication off the ground by sharing it with someone you think would appreciate it.

I’ll be back next Wednesday with your weekly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Until then, keep 💪.

Excellent article, Alia. As a writer of fiction that takes place in Victoria, and in which place is a key element, the interplay between what a place means to its current inhabitants, and its far more complex layers of meaning for Traditional Owners is one that fascinates and troubles me.