Welcome to Mind Flexing, your fortnightly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Strap on your boots (or put your feet up), take a deep breath, and let’s get flexing.

The tree died when Carol was eight. She had loved that gum. It must have been at least 80 years old.

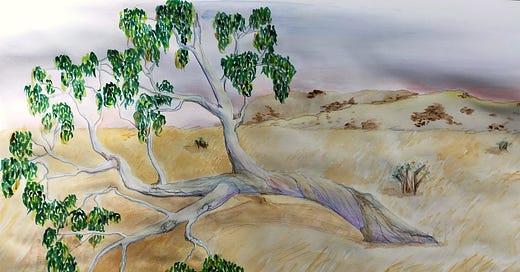

She’d walk along its thick silver trunk, which grew as if someone, something, long ago had knocked it over so that it hovered just above the ground then curved upward in a burst of gnarled branches; she would sit there, legs dangled over the side, brushing against its bark that swirled and twirled around the great tree’s body. From there, she could see right across the paddock, through the cattle and up the rock-pocked hill. Beneath the trunk, amid the branches that arched downward, was her house, the kind of house that formed in children’s minds, with no walls or windows, but a kitchen of leaves and assorted sticks for tea parties and dinners. She was always at the tree. It grew a few skips from the white weatherboard house, separated by a barbed-wire fence and bridged by a timber stile built especially for Carol by her father. Its leaves were long, each curved ever so slightly in one direction or the other, except for the branch with circular leaves of silver green, which looked like it belonged to a completely different tree, yet didn’t.

Three years before it died, the drought had come. First the grasses in the paddock had browned, then been eaten down to stubs. In the second year, the creek dried up and the paddock turned to dust. That’s when the tree triaged its first limb, cutting off sustenance so that the leaves fell one by one like teardrops from the dried, cracked branch, which stayed attached like a bone protruding through its skin. Limb by limb, the tree went numb, and by the end of the third year when the bore dried up, it was dead; the silver drained from its lifeless body; a ghostly grey figure lurched across a valley of death.

Even so, as she grew, Carol would go to her old friend and sit with it on an amber evening when the sun had retreated but the air still warm, and listen to the silence. It was unnervingly silent, the sort of unease that warned every inch of your being to run. But to where? There was nowhere to go, for them at least. The cockatoos had long gone, having flocked to towns and cities and anywhere there was water, and the wallaroos had left in thirst. Even the crickets had abandoned her. The last of the emancipated cattle had been sold for a pittance, less than what it cost to feed them, her father had said (the bank manager had been to see him). He spoke less and less these days, and it was about this time Carol’s mother got a job at the general store two towns over. Two days a week was all the manager could spare, barely covering the petrol, but they made do on the generosity of others.

Year after year, so went Carol’s childhood, her eyes following the cracks in the scorched earth back and forth and around, tracing the lines of hexagonal terracotta tiles that paved the landscape as far as she could see. And there was the tree among it, its limbs now strewn like broken bones beneath its failing trunk.

Carol was 19 when the drought broke; it was if she had never seen rain. God it was marvellous, and the petrichor that rose from the ground was intoxicating. It steamed as she breathed it in and exploded within her lungs and she felt that if she kept breathing she would float up into the sky. Then she ran past the old tree and through the paddock, barefoot in the mud, and knew that every living thing within the storm’s radius was at that very moment outside, together, in the rain. It rained for two whole days. The following week, tiny green shoots began to appear across the land, and within a month, the landscape was fluorescent.

Carol moved to the city that year to work as a receptionist at a small law firm specialising in wills and probate. She liked the urban desert with its reliable tap water and cacophony of chatter, and patched it like a band-aid over the internal scar left by the death that had spread over the land and its people like a silent disease. She was never in a rush to return home and on occasion when she did, she was so discombobulated by the fertile land of golden grasses bowing in the breeze that she couldn’t quite believe it was one and the same as the place she had spent too many years yearning. And yet, there was the tree, still there. Two Christmases had passed before she noticed the change. Returning home as she did at that time of year, she had climbed the stile like so many times before and pulled her body up onto the trunk. It took a great deal of staring with little squinty eyes and a mouth wide open before she, heart pounding, realised the old tree was alive. There, bursting from its base was a silver branch—full of life and leaves, reaching upwards—and another enveloping the old cracked trunk like a new skin. It was the old tree—not a new sapling grown from a seed, but the tree, resurrected from the dead.

Each time Carol returned, the new skin had crept further and further, swirling and twirling around the old trunk and periodically shooting a new branch skyward so that the tree now resembled a colonnade over an arched bridge. She sat there again 10 years later, this time with her fiancé, Steven, a city-boy mortgage broker with a fast car and sometimes, a moustache. She told him how the tree had been dead for 11 years then resurrected, and she showed him the old trunk that peeped out from one end like a wound. Steven smiled, and holding her hand, said it was indeed a cool tree, and they sat there watching the cows graze before the rock-pocked hill. Their children, Molly and Stu, would play there too, under the branches that grew and thickened with each passing year.

By the time Carol’s father died of a stroke, all signs of the old trunk had been submerged under the new bark. She visited more frequently then. Her mother was ailing, and she would sit with her on the verandah overlooking the tree and, sipping their tea, compare grey hairs. When she returned for the funeral five years later, she cried a drought’s worth of tears, then packed her parent’s belongings, the cutlery and the twice-used china, their old clothes, the shoes never to been worn again, and the green glass vase that she would keep for herself, but that would probably one day, after her own death, lose its meaning and perhaps forge a new one, it being found among an op-shop’s bric-a-brac and sold for a dollar to someone who liked its mid-century styling but had no idea how old it truly was. Then, after listing the house for sale, she opened the gate to the paddock (for the stile was long gone) and sat on the tree for the last time.

A nuclear family came to look at the house—a husband, a wife, a boy, and a girl. The children were young and ran round the yard poking sticks into bushes and chasing the bees. They interrupted sentences; come and look at this beetle; we want to climb the tree, they said. Opening the gate, the agent let them into the paddock, and the father, remarking that it was indeed an odd-looking tree, like someone, something, long ago had knocked it over, wondered aloud how old it must be; at least 40 years he surmised by its smooth silver limbs. The children were swinging around its columns, working their way along the trunk, laughing. The agent, looking over, clicked his tongue and nodded. Yeah, seems about right, he said. And then he sold the house. ♦

Note: Eucalypts really do have this amazing ability to return from the dead after drought, fire or felling due to lignotubers that can remain incubating in the base of the tree, reportedly for decades. They are truly remarkable survivors.

Etymology Monday

For those who missed it on Substack Notes, this week’s word is a source of inspiration…

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment, click the ❤️ button, or share it with someone who would appreciate it. I’ll be back in a fortnight. Until then, keep 💪.

What a magical story! I love it on all levels of metaphorical and physical lasagne. Well done!

My first thought was that you’re a born storyteller, but then I realized that was simplistic of me and unfair to you in its failure to give proper credit for your hard work, your life that I’m sure has been an adventure lived well to this point, your keenly developed powers of observation, and the genuine care you demonstrate for the earth and all its living things. Writing of this quality, clarity, and emotional depth can only be the product of years of discipline, study, perseverance, and the constant practice of your craft. You make it look easy, but I’m sure that reaching the point you’re at has been anything but. Thanks for this story and all the blood, sweat and tears that you’ve put in to be able to do what you do!