Part 2: How to change the world

#46—A counterculture poet inspires the most iconic anti-war movement of our times.

Welcome to Mind Flexing, your fortnightly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Strap on your boots (or put your feet up), take a deep breath, and let’s get flexing.

Missed Part 1? Click here to read it.

Change doesn’t happen in isolation. It moves like a clock, the hour steadfast in its appearance, our eye distracted by the incremental movement of the minute hand and the seconds ticking, while underneath a cog turns another, and another. The pendulum swings. It’s not until sometime later, when we glance back, that we see the hour has moved on.

Everything is interconnected; every person, every idea, every living and non-living thing that exists is a cog, turning and being turned, shifting culture like an amorphous organism, an organism that’s made up of so many ideologies and clashing beliefs that it’s hard to believe it’s a singular noun, and yet it is. Culture. A word that dually describes a way of life, its values and beliefs, as well as the arts—literature, visual art, music and theatre—two distinctly separate definitions entwined so tightly that one cannot exist without the other.

The arts connect us to culture, help us understand alternate viewpoints, inspire ideas and new ways of thinking, and as each cog turns, they instigate change. Their ability to attach to emotions means they store well in our minds so that long past the hour, it’s the music, the literature, the visual creations and the theatrics that remain stored in our collective memory. And when we look back, decades later, we can read this living, shifting organism like a history book.

In many ways, what we create is determined by the cogs that turn us. It’s a concept explored by the American record producer Rick Ruben in his book The Creative Act. Ruben, who has produced many of the world’s leading bands and singers, from the Beastie Boys to Johnny Cash, says:

“We are all participating in a larger creative act we are not conducting. We are being conducted. The artist is on a cosmic timetable, just like all of nature. If you have an idea you’re excited about and you don’t bring it to life, it’s not uncommon for the idea to find its voice through another maker. This isn’t because the other artist stole your idea, but because the idea’s time has come.”

It may well be that an idea has its time, but who brings that idea to fruition and the creative form it takes can make a difference. For a less influential artist, the creation may be one of many small cogs turning through time, influencing the influencer; on a grander scale, and with a dash of synchronicity, a creation could stoke a chain reaction of the kind we explored in Part 1 of this series, when the scientist Leo Szilard picked up HG Wells’ novel The World Set Free and saw within it the horrific future.

Or it could be the moment in 1965 when American poet Allen Ginsberg, overcome with anxiety about the Hell’s Angels’ plans to attack anti-war protestors in California, popped some acid and went for a walk by the ocean. It was a moment that, not necessarily changed the course of history, but rather shaped the way it unfolded in time and imprinted on our memory.

The cogs were turning at warp speed in 1960s America. Following the shock of JFK’s assassination and tensions of a Cold War, a pent-up resistance to the status-quo broke free with movements of all kinds—civil rights, human rights, women’s rights, racial equality, sexual freedom. Culture was becoming more aware of the world, of its possibilities, and of psychoactive drugs. It was a counterculture powered by youth and steered by the educated class. It was rowdy, stayed up late, played loud music and demanded change. It was exciting, and as you can imagine, it was an unwelcome change for many.

Amid this cacophony in April 1965, President Lindon Johnson announced the ‘need’ to ramp up U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. The war, already 10 years in, had largely evaded public scrutiny, but as more troops were deployed, an anti-war movement sprung up in university campuses around the country. In November that year, the Hell’s Angels, believing protesters to be Communists, vowed to violently attack anyone attending an anti-war demonstration organised by students at the University of California, Berkeley. Fear was growing and hysteria erupting.

To escape it, in the week before the protest, Ginsberg—the famous Beat poet and activist known as the voice of a generation—went for a walk to clear his mind. He later said:

“The day I took LSD was the same day that President Johnson went into the operating room for his gallbladder illness. As I walked in the forest wondering what my feelings toward him were, and what I would have to say in Berkeley next week—the awesome place I was in impressed me with its old tree and ocean cliff majesty. Many tiny jeweled violet flowers along the path of a living brook that looked like Blake’s illustration for a canal in grassy Eden; hug Pacific watery shore.

I saw a friend dancing long haired before giant green waves, under cliffs of titanic nature that Wordsworth described in his poetry, and a great yellow sun veiled with mist hanging over the planet’s ocean horizon.”1

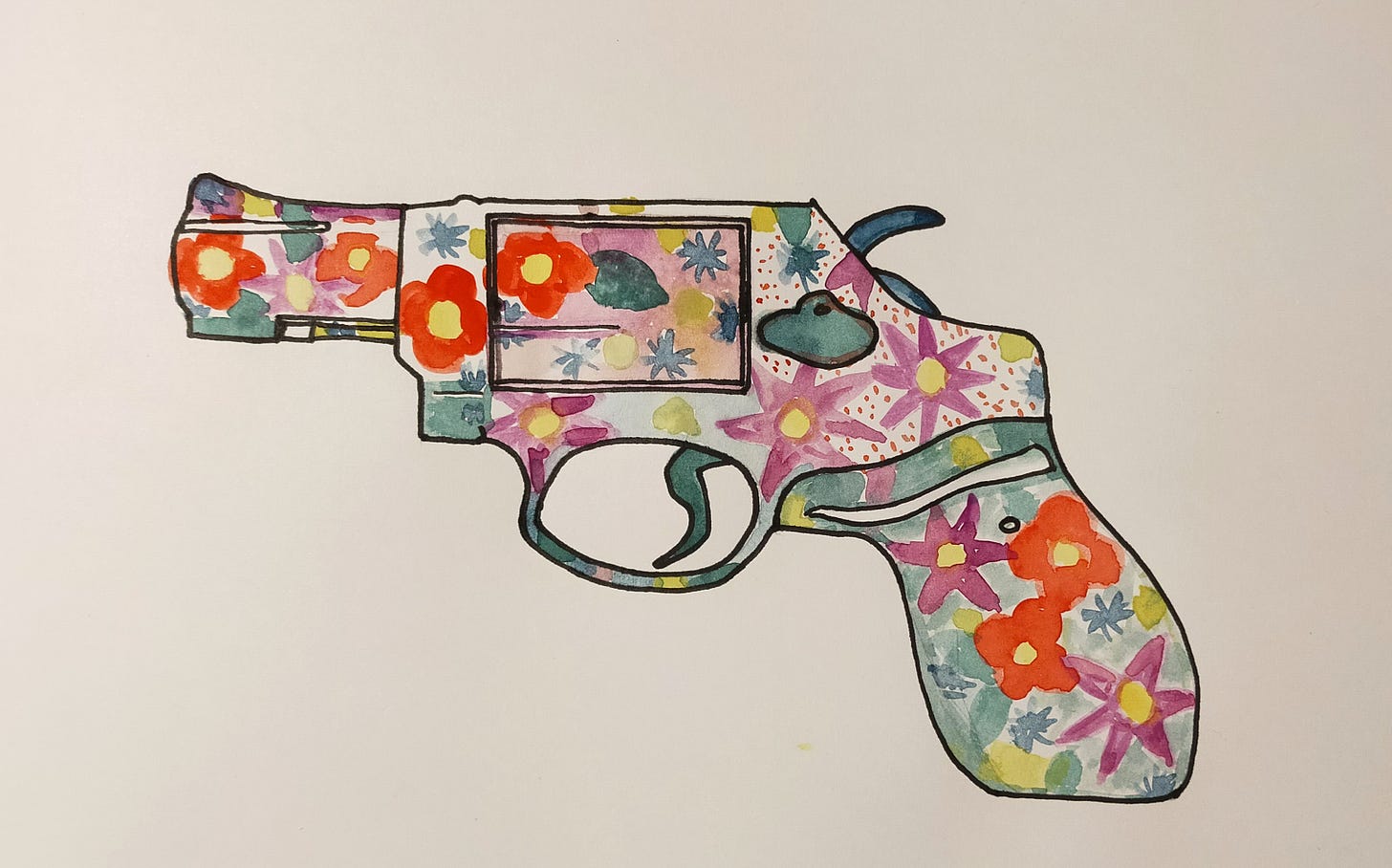

When Ginsberg returned from his walk he penned some very specific instructions for the protest’s organisers. There was to be a parade full of flowers, dancing, singing, music and non-violence; there were to be flowers on the front line, flowers as barricades, flowers to give to bystanders, to police, to the Hell’s Angels. There was to be peace. Word spread, and when the day came, so did the flowers. The Hell’s Angels stood aside, and Flower Power was born.

Flower Power captured the imagination of the masses and inspired artists to add their own creations to the moment, forming the most iconic anti-war and cultural movement of our time. It was immortalised by French photographer Marc Riboud in a heart stopping image of 17-year-old Jan Rose Kasmir holding a chrysanthemum between her face and the bayonet of a soldier during the 1967 March on the Pentagon. It shifted into the broader hippie counterculture, which also adopted Gerald Holtom’s anti-nuclear symbol for Peace. It was time to make love, not war, and in 1967 as many as 100,000 flower children, beatniks, artists, musicians and writers converged on the San Fransico district of Haight-Ashbury in a cultural phenomenon that became known as the Summer of Love. Capturing the moment in song was Scott McKenzie’s San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers In Your Hair).

The draft effectively halted in 1972 and with it, the mass gatherings and flowers faded into the final years of the war, which ended in 1975. Did flower power end the war? Not really, there were many cogs turning on that front, but it did awaken the world to the devastation of Vietnam and placed pressure on the U.S. and its allies to withdraw.

Ginsberg’s idea was like lubricant on the many spinning wheels of change, inspiring the young, the disenfranchised, the artists, writers, theatre and film, designers, photographers, and musicians, to move in unison, and through the legacy of their creations, and in society’s collective memory, flower power formed a lasting impression on our attitude toward the Vietnam War.

Next, in Part 3 of How to change the world, I explore activism in the arts and how to overcome prejudice.

Things I enjoyed on Substack this week

Writing through the madness of our times—by Elif Shafak

An exploration of Tulipmania and how it relates to our times.

The Witch And The Oak Tree—by Jonathan Foster

Another mania takes hold.

A long walk: or…—by Maggie Mackellar

On how to avoid the mania.

Etymology Monday

This week I delved into two words with a common ancestry: journey and journal.

Virginia Woolf

Here’s something a little different from me… Tash from Wolfish! very kindly invited me to chat with her about a short piece by Virginia Woolf. It was wonderful to revisit Woolf in my mid-40s having last binged on her words a good 25 years ago. Coming back a bit wiser, and considerably older, I’ve found the experience to be quite revelatory. Tash and I spoke about a short essay called Street Haunting: A London Adventure, which I chose because of the breadcrumbs Woolf scatters about herself as she walks. And I love the name. I hope you enjoy haunting the streets with Woolf as much as we did.

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment, click the ❤️ button, or share it with someone who would appreciate it. I’ll be back in a fortnight. Until then, keep 💪.

Deliberate prose: selected essays, 1952-1995, by Allen Ginsberg

Excellent stuff, Alia.

Who knows what waves emanate from the smallest actions to expand across the largest areas, connections and networks, a kind of creative mycelium. For me, often, the artists have a clear eyed view of things, from standing on the outside looking in, instead of identifying with concepts and ideas and thus subconsciously defending them.

IN all this chaos I found this to be very optimistic. Thanks :)

Oh wow, I love this! The arts often feel so... powerless. You never know who and how it will touch and make a difference, you can only see it in hindsight. What a wonderful encouragement to keep on drawing and sharing my art. You never know if it will set someone in motion or encourage to keep going...