Welcome to the first edition of Mind Flexing, your weekly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Strap on your boots (or put your feet up), take a deep breath, and let’s get flexing.

There’s nothing like a throw-away line to get me thinking. Small details, left undefined and semi-detached, cause an itch that must be scratched immediately, usually with the fastest remedy, Google.

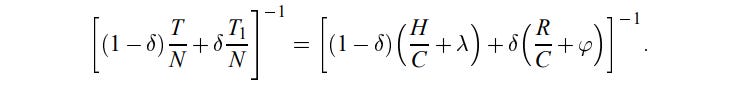

And so it was that I found myself reading A Mathematical Theory of Communication written in 1948 by mathematician and electrical engineer, Claude Shannon. Well, reading what I could of it; I don’t speak advanced mathematics.

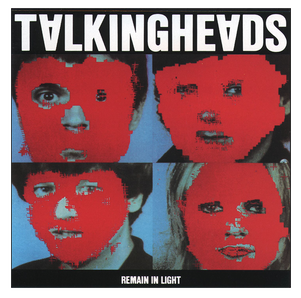

But there I was, trying. An itch had developed in an interview with the band Talking Heads and I scratched it.

You’ve probably read a bit about Talking Heads lately because of the re-release of Jonathan Demme’s 1984 concert film Stop Making Sense — a film of the band’s 1983 concert tour. Talking Heads had put old grudges aside to discuss the film with The Age’s music journalist Michael Dwyer when “suddenly”, as Dwyer explained, they were talking about mathematician Claude Shannon’s Information Theory.

“The amount of information is the inverse of the degree of expectation,” bandmember Jerry Harrison said on the topic, a segue from their discussion on the complexity of modern stage lighting cues and brain synapses.

Profound? A bit. But then you would expect that from a 48-year-old New York, new wave, post punk, experimental art pop band.

Even so, I dislike profound statements interjecting to make a story Stop making sense, and this one was like Speaking in tongues, taking me on a Road to nowhere.

Curiosity aroused, I jumped in a wormhole to 1948 and went looking for what the quote might mean, and for a reason as to why a New York, new wave, post punk, experimental art pop band found Shannon’s mathematical theory so interesting.

Bits of information

The words of Shannon’s Information Theory soon began to look very familiar — ‘bits’ and ‘bandwidth’ and ‘code’. They weren’t common in the lexicon of 77 years ago, but to us in the Information Age, they’re like a pair of well-worn shoes.

Turns out, Claude Shannon was a rather seminal figure. Not only was he a unicyclist who could juggle, but his Mathematical Theory of Communication lay the groundwork for our computer-based world of communication. His paper demonstrated how a ‘bit’ of ‘information’ could be sent over a noisy ‘bandwidth’, like a telephone line, and decoded correctly by the receiver.

(A light bulb moment,

for all I know, a brain synapse,

and the acronyms IT

and ICT

moved into new dimensions.)All very interesting, but Harrison’s quote still didn’t fit. Nowhere in Shannon’s work could I see how an amount of information was the inverse to a degree of expectation. Granted, the math was beyond me. But did it really matter? I felt I understood the essence of what Harrison was saying, or rather, Dwyer’s interpretation of the discussion. If I were a fly, I may have been able to sit on the wall and decipher the information myself.

Thankfully, I’m not a fly (at least in my own opinion), so instead I stared at my computer screen. Stumped.

The irony of the situation didn’t escape me.

Shannon’s enduring life’s work used mathematics to demonstrate how to create a reliable system of communication. A system that could be controlled. A message, whose sender could be sure that the recipient would receive a true copy of that information.

What was, and is, uncontrollable is how we imperfect humans interpret that information. Each being has a unique combination of influences and experiences that informs its understanding, resulting in words that elicit feelings and memories beyond the control of any dictionary (and which dictionary, anyway?).

We lose control of the words we speak as they leave our lips; the lines we pen form their own meanings inside the minds of those who read them. Unlike mathematics, we cannot control the deciphered message. Our creations, our words, our art — anything birthed into this world — goes forth on journeys of their own, where the number of interpretations is the sum of information, represented by ‘x’, times ‘y’, being all who encounter it: ∑xy

(And that doesn’t account for third-party unfurling of the message, which increases the variance in interpretation exponentially.)

Shannon could reliably transmit a message, but he couldn’t control how Harrison interpreted his words. Harrison couldn’t control what Dwyer understood, who in turn couldn’t control my thoughts. And gosh — what on earth are you thinking right now?

Revolution and resistance

Meaning, as determined by the reader, is an idea that was popularised in literary circles by French writer Roland Barthes, who released his essay, The Death of the Author, into the wilds of our minds in 1967.

Of course, it had to be in France — birthplace of bourgeoisie liberalism; cooking pot of the French Revolution — where the democratisation of literature would arise. Barthes argued against modern literature’s ‘capitalist’ obsession with picking apart an author’s biography to critique their authorial intent. Instead, he declared that the meaning of any text could only lie with the reader. Essentially, he said attempting to decipher an author’s intended meaning limited the range of meaning those words could have.

“Once the Author is gone, the claim to "decipher" a text becomes quite useless. To give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing,” he said.

As Dr Oliver Tearle, lecturer in English at Loughborough University, UK, explained it:

“Writing is a performative act which only exists at the moment we read the words on the page, because that is the only moment in which those words are actually given meaning – and they are given their meaning by us, who interpret them.”

It’s an interesting theory. But is it valid? There are certainly many examples of Barthes’ theory in motion.

One example that comes to mind occurred just recently in the visual arts world. A street mural in Melbourne was removed for being widely interpreted by the public as antisemitic, despite, it was reported, it not being the intention of the artist to create an antisemitic work.

Was the work antisemitic? As Barthes would argue, the work’s meaning lies with those interpreting it, so yes. The creator may disagree, but unlike mathematics, the message can’t be controlled.

Not only is the message uncontrollable, but words, their meanings, culture and place, shift with time.

Take for instance Anna Funder’s acclaimed new book Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life, which tells the story of Eileen O’Shaughnessy, George Orwell’s wife of nine years. Some reviews have criticised Funder for imposing modern cultural expectations to a time past.

Was Orwell a misogynist, as Funder has suggested? Her interpretation of things that were said, and left unsaid, (and our interpretations of what she said) indicates, yes, and Barthes would agree.

Funder addressed the criticism in a recent interview with Emma Conners in the Australian Financial Review, saying:

“Does that mean we should have no progress ever? Would we not use our own ideas to look at slavery? Or colonialism?”

Cake, anyone?

So, we see that a message can mean something different to each individual. It can also develop a prevailing meaning in the social consciousness, and change meaning over time. But Barthes went a step further. He said for the reader’s interpretation to be taken seriously by critics, the author must die. Well, metaphorically, at least (although a dead, dead author would be even better).

“… the birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the Author,” Barthes surmised.

It’s a stark theory. And while just a metaphor, as writers, are we truly at ease with that notion?

We write with intention. Are we content to let those intentions rest in peace the moment our words go forth into the world?

Are our thoughts, our words, ours? Barthes argued they are not; that they are merely rearrangements of things that already exists, and therefore the author is unimportant.

He surmised:

“We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single 'theological' meaning (the 'message' of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture.”

An eerily familiar argument for our day and age. Indeed, we Author-Gods justify our existence by describing Artificial Intelligence in much the same way.

Barthes’ theory was thought provoking and radical, which is why it is still discussed today, and found in wormholes that form in Talking Heads interviews and mathematical theories of communication.

But the theory had a major weakness. For it to thrive, Barthes conceded he needed a revolution — a revolution that never came. Then, as with now, readers like to be fed cake.

The relationship between reader and author is immortal; within it lies anguish, fascination, mystery, and much to be deciphered. And perhaps that is the attraction. Meaning can’t be controlled. It is up to each one of us to untangle the web of information, to decode the author’s intention, and form a conclusion that is ever tinged with uncertainty. We’ll be back for more, forever looking for clues.

The reader’s interpretation of meaning is paramount; the author needn’t die for it to flourish. The existence of the author doesn’t limit a text’s meaning. If anything, meaning expands like a river breaking its banks, exposing the paradox in Barthes’ theory.

For such tragedy can be felt in the lines of Mrs Dalloway when you see Virginia Woolf’s troubled soul stepping into the cold waters of the Ouse. A tethered ache hangs over Richard Flanagan’s Death of a River Guide when we picture death staring the author in the face, trapping him for hours in the wild rapids of the Franklin before releasing him, forever changed.

The brilliance of a good story is that it can be enjoyed without such knowledge; the words on the page are all that are needed. But for the reader who dares to go looking, the intrigue of the author is magnetic. Barthes cannot deny us that.

And so, here we are. Reader and writer, coexisting. Is one view more important than the other? Is the author’s intent greater than >, less than < or equal to = the reader’s interpretation?

The answer is probably +/-, ‘same as it ever was’.

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment, show some ♡, or help me get this new publication off the ground by sharing it with someone you think would appreciate it.

Enjoy the holidays and have a happy New Year. I’ll be back here on Wednesday 10 January 2024. Until then, keep 💪.

Excellent points for all readers and writers to consider.

My personal take on the primacy/irrelevance of the author’s intent is to reject it as a false dichotomy.

“The author’s intent doesn’t matter,” is a route to lazy, self-satisfied reading, a refusal to of the reader to accept the work’s challenge.

“The author’s intent is all that matters” is a route to arid, self-effacing academicism, and this, I assume, was Barthes’ target.

Writings are provoked by a context, and understanding that context enriches our appreciation of the work. Writings, like all works of art, elicit a personal response from the beholder, otherwise why bother reading?

We can (and I would argue, should) do all the things.😊