Welcome to Mind Flexing, your weekly thought expedition to everywhere and anywhere. Strap on your boots (or put your feet up), take a deep breath, and let’s get flexing.

I went for a walk last week, my first in this season’s winter grass. I look forward to this time of year when the grasses, having shed their summer seeds, lay down to rest on the forest floor, parting to reveal their secrets. They always have secrets.

It's easy to be distracted by the vibrant colours of the valley in May. Autumn’s last leaves are clutching the branches, flickering in the sun’s backlight like tiny red and yellow lamps. Inevitably, they fall, exposing skeletal branches that signal the fast approaching winter. In the evenings, I run beneath the eucalypts that line the wire fence collecting fallen twigs for kindling. I run because time is never on my side. Is it ever? I light a fire to warm the house into the early morning when the temperature drops to near freezing, then let it burn out before the sun rises and radiates warmth through the windows once again.

Autumn is such a beautiful time in the High Country. It’s a colonial beauty; these deciduous trees come from places far from here. Sometimes I feel guilty for revelling in them. Even so, the mélange of foreign and native trees forms a uniquely Australian scene.

When I look beyond the vibrant colours of the valley I see the bush-clad mountains also changing. The knee-high waves of stiff summer grasses have subsided, mellowing into a soft carpet beneath the canopy of peppermints and brittle gums. Fantastical fungi, awakened by the chill of night and dew-drenched mornings, decorate the forest floor and decaying wood.

I love the winter grasses; a green carpet to adventure, settling to reveal mountainsides of hidden trails. Unlike formal trails, these trails are narrow and delicate, sometimes worn to a thin line of dirt, but frequently just flattened grass. Sometimes they disappear. Some are ancient, some are well-used paths to vantage points, many are carved by dirt-bikers and mountain bike riders, but more than these combined are the animal tracks, which spread through the bush like spiderwebs. You can follow the animal tracks almost anywhere if you have your bearings and don’t mind detours around unexpected melaleuca thickets or rocky drop-offs.

To be fair, many of these informal trails are discretely discernible in the overgrown summer grass, but this is Australia and the long grass of summer is for the snakes—eastern browns, tiger snakes, copperheads and black snakes. And so, I wait for the snakes to grow docile and the grass to bend down and show the way, as it does now.

So I went for a walk with my husband, each of us carrying a child, to a place that I’ve been wanting to visit for more years than I should have let pass. A hidden graveyard of unmarked graves in the bush a little way up the base of a range; hidden because there is no formal recognition of this graveyard, it’s not on the State Heritage Register, there is no sign to point the way and no official path to get there.

We had been told to look for a narrow track opposite a road sign on the main road, and sure enough, a grass clearing wide enough to be a two-track rested between the scrub. It funnelled us into a blackberry thicket, cut through by a dedicated hand to be just wide enough to squeeze with only a few scrapes. There are many trail fairies in these parts. We hoisted the girls up high and made our way through the gate of blackberry to emerge into a tidy forest. A path no wider than my foot cut through the grass and up the hillside. It’s infrequently used, but being old, it was easy to follow—the ground beneath it having been flattened for at least 160 years, probably longer.

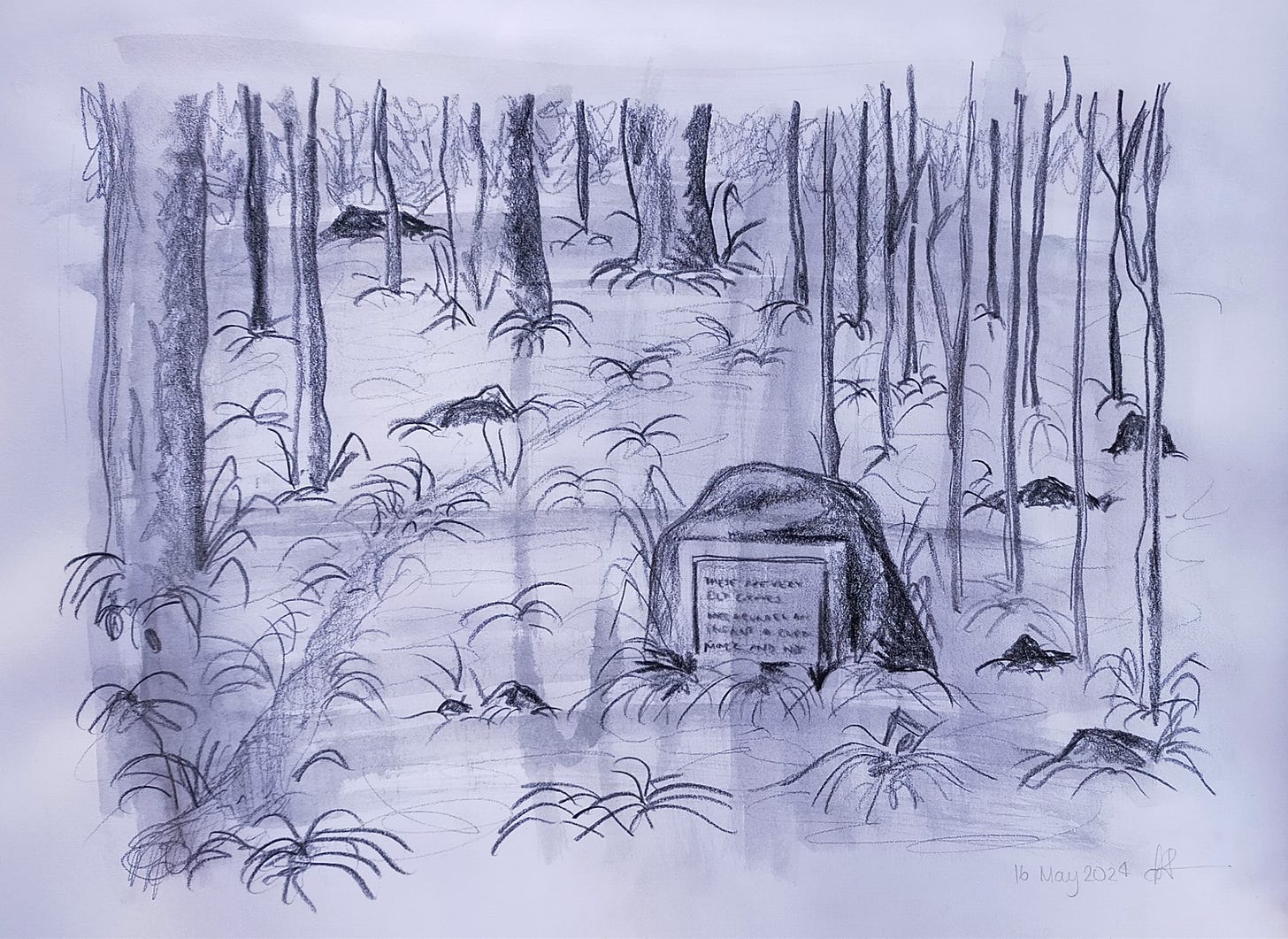

We wove up the hillside beneath the eucalypt canopy and in less than 10 minutes reached a partial clearing where sat a small gravestone-sized rock bearing a meatal plate placed in the 1970s. Pushing the grass aside so we could read it, it said:

These are very old graves, probably here before the establishment of the Bright cemetery.

Mrs Arundel and infant child.

A Cornish miner.

Three Chinese, Yak Wow, You Hoy, Ah Looey.

Who else lies beneath this soft bed of grass? There were no gravestones, just a small clearing no more than 20 by 20 metres, and already the bush was reclaiming it, shooting dozens of spindly trees toward the sky. Somewhere, beneath the grass and the rocks, lying between the roots, were the remains of pioneers attracted here by the discovery of gold in the 1850s.

It was a strange feeling to be walking on the remains of the dead, unsure of precisely where they were. I found myself mentally apologising for stepping on them.

And then I began to think it strange for feeling so, because really, unmarked graves are everywhere. We live among the dead, we’re mostly unaware of it. There are many more unmarked graves in this valley—in this country—than the ones before me; lost graves of almost a thousand goldminers who died of disease in an adjacent valley, and there are much older graves too, tens of thousands of years’ worth of burial sites, the knowledge of which has largely vanished with the First Peoples who perished in the Frontier Wars or suffered under subsequent assimilation policies. Then there are the dead of the Frontier Wars themselves, which were so brutal in these parts. There are graves of those killed who were buried with love. There are mass graves. And there are the resting places of those left to lie where they fell. There are places where bones were displayed like trophies. Many of these final resting places lie on farms, in the paddocks, alongside houses, a fishing spot by the river. There are no memorial stones, nothing to remind us of these lives. We go on living around them, unaware of these stories in a country still resisting its past.

I look at the small memorial plaque in the winter grass and think about the mother and her child, the Cornish miner and the three Chinese pioneers. I think about how with a little knowledge and a plaque, we choose to be reverent.

Then I turn, holding my littlest, and follow the old track down the hill back to the colours of the valley, and to my home. And there, gazing out over the paddock, I think about the others.

Things I’ve enjoyed reading on Substack this week

Alice Munro—by Margaret Atwood

In memory of the formidable writer Alice Munro, who passed away this week. Part of Margaret’s tribute to her old friend is behind a paywall, but a significant part isn’t and it is a lovely read.

People Will Come, Ray—by Paul Edward

I’ve followed Paul through the darkness of winter into a new dream-filled light. Creating food as art, with love, in a restaurant by the Sassafras. I would come.

Marc presents a beautiful collection of photos and thoughts from the alpine mountains northeast of me.

Thank you for Mind Flexing with me. If you enjoyed this essay, please subscribe, comment, click the ❤️ button, or share it with someone who would appreciate it. I’ll be back next week. Until then, keep 💪.

A very poignant and thoughtful post, Alia. I’m fascinated and dismayed in equal measure by how much this land we live on has been altered in the last two centuries, as much by neglect as exploitation. I only ever go to the High Country as a visitor: I envy your intimate daily connection with the mountains. But hey, I chose the coast, and that has its own charm.

Thank you Alia, your words so elegantly combine both the beauty and heartache of our home landscape. I find this time of year brings a sense of both wonder and contemplation x